The Bittersweet Magic of Middle Grade Fiction

Awe, grief, and how His Dark Materials made a doorway for this bookish adolescent

I was a bookworm as a child. I graduated from picture books to Nancy Drew and Wishbone classics at a pace that was no doubt a challenge for my elementary school librarian (she eventually pointed me down the hall to the middle school library with a cheery “good luck!”). When the Wishbone classics got too simple, I graduated to Louisa May Alcott and Charles Dickens. I read voraciously as a kid, in just about every genre. I particularly liked mysteries; logic puzzles I could pull apart and reason out were so satisfying to my pre-adolescent brain.

But somewhere around fourth or fifth grade, I found myself gravitating toward science fiction and (especially) fantasy. I still read pretty widely, and I still loved the structure of a mystery (Agatha Christie was a favorite at the time, though I never really got into Arthur Conan Doyle), but this was the age when I became hungry for speculative fiction above all else. Tamora Pierce’s Song of the Lioness series, Robin McKinley’s fairy tale retellings, the Chronicles of Narnia, T.A. Barron’s Merlin Saga… these were the books that did more than keep me occupied: they soothed my soul in ways that I couldn’t articulate at the time and am only learning to identify now.

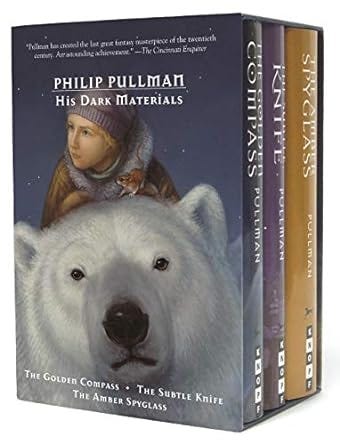

Above all the series I read at that age, one stands above the rest. A series so powerful it resonated through my life in ways I’m only just starting to become aware of. So cathartic that even now, as an adult, I ugly-cried all through pretty much the entire last season of its television adaptation. A series that seems to me to hold magic in its words to this day, and that remains a signpost to me on the ways speculative fiction can access truths that are buried so deeply we need metaphor to get at them.

This series is Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials.

I remember when the third book in this series came out. I was a month shy of my thirteenth birthday, essentially the same age as the protagonists of the series. Some of my strongest memories of that age are of reading that book. I remember feeling alive, awake in a way I never had before. Like the words had stirred something loose in me, an awareness so sharp it cuts all the way to the present day.

So what is it about this series that encapsulates the magic of speculative fiction? I’ve spent the better part of two decades wondering the same thing. I think I’m starting to have an idea.

(spoilers ahead for His Dark Materials)

The daemons

One of the fantasy elements of His Dark Materials is that everyone has a daemon—a physical manifestation of the person’s inner self. Before puberty, a person’s daemon can shape-shift into any kind of animal, but once the child becomes an adult—and presumably settles into some sort of stable adult identity—the daemon settles on a permanent form. While Lyra—the central protagonist—can be impulsive and hot-headed, but through her daemon Pantalaimon (Pan), we see her deep compassion and loyalty. This is one way that daemons provide a depth and maturity to the story. Without saying how Lyra’s upbringing was traumatic to her—she was raised by the scholars at Oxford, left there by a man she believes to be her uncle, but later learns is her father—we can see in how she interacts with Pan that she wrestles with trust and acceptance.

The daemons are often a useful shorthand for personality or lifestyle. They can explain a lot about a new character introduced—provided that character is an adult whose daemon has settled into a permanent form—without many words. This is a construct so simple, and could be just employed as a useful writing trick. But Pullman doesn’t just use it as a cheap shorthand—the way he writes the relationship between one the story’s chief antagonists—Mrs. Coulter—and her daemon is nothing short of brilliant.

Mrs. Coulter enters the story when she invites Lyra to become her assistant. She is an academic, studying why a mysterious quantity called Dust—visible only using special cameras—seems to gather only on adults, but not children. The theory espoused by the Magisterium—the political and religious authority for whom Mrs. Coulter works—believes Dust is evidence of original sin, and it’s Mrs. Coulter’s cruel experiments that leads them to discover that by separating a child from their daemon, the settling of dust that occurs at puberty can be prevented. This nearly always results in the death of the child, or at the very least, the loss of their mind. (But more on Dust shortly). It would be easy to see Mrs. Coulter as a one-dimensional villain—cruel beyond all belief—but what makes her fascinating is her daemon.

Like Mrs. Coulter, her unnamed daemon is beautiful, cunning, and charming. A golden monkey, he inspires awe and fear in those who see him—and his cruelty is evident before hers becomes obvious. He never speaks, which is rare for daemons, and he and Mrs. Coulter can be farther from each other than is considered natural. This separation is at first a curiosity, and something that makes Mrs. Coulter fascinating and powerful. But eventually, it starts to become clear that there is more to this than parlor tricks. While Lyra and Pan have a playful though sometimes combative relationship built on mutual respect, Mrs. Coulter and her daemon almost seem like two enemies hitched to the same revenge plot. They have to deal with each other, but the experience is as painful for them as it is for the people who cross them. And this nuance is brought to life devastatingly by Ruth Wilson in the TV adaptation.

We see in the daemons the complex relationships that people have with each other. It states clearer than words that sometimes a villain’s greatest foe is her own inner self.

Dust

One of the first rules of writing for an age group is that your characters—at least the ones the readers are meant to identify with—are the same age as your audience. And so it is that Lyra and the other central protagonist, Will, are somewhere in the 11-14 range throughout these books. It just so happens that these are the final years before Dust settles on humans—and before daemons settle into a permanent form.

Depending on who you ask in the books, Dust is Original Sin made manifest, or it’s the wisdom of age, or it’s evidence of consciousness. It’s an invisible element that makes sentient life possible—that is, itself, sentient life. And the transition from a child who is mostly ignored by Dust to an adult who attracts it is a central theme of the story.

These many definitions bring out the bittersweet transition to adulthood that happens at this age in the main characters and the readers. Dust is a thing that comes with first love. It’s also a thing that comes with the disillusionment of discovering all the ways justice is not served and mercy is scarce in the world. It’s the power of wisdom and independence, and it’s the discovery that magic isn’t real and all your heroes are just sad, mortal humans who make mistakes just like you.

Lyra and Will are at this point of discovery. It’s not that their lives were joyous and blissful before this awareness, but rather that the lessons they learn in their journeys are bittersweet and imperfect. And if this isn’t those painful, beautiful pre-pubescent years, I don’t know what is. At that age, you become aware of everything you could be. And everything you could lose. You’re not yet grown, not yet touched by those qualities that make you grown. But you begin to perceive them.

Death and Goodbyes

Years don’t just accumulate, they accelerate. I remember at this age starting to feel like time no longer languished, it burbled past, heading toward a rushing, crashing falls. And it’s a one-way stream—the current is too strong to push backward.

The awareness of death, true awareness, is part of becoming fully conscious. And Lyra and Will have to face death in a literal sense. In the third book, The Amber Spyglass, they venture into the land of the dead itself. As part of this journey, they must leave their daemons behind. After all, what is death but the separation of soul and body?

I remember this separation in the books. I remember it feeling as immediate in my own body as it was to Lyra, and especially to Pan, her daemon who was such a perfect window into the soft interior of this spunky, fiery young girl. This journey changes Lyra and Will both, and it changes their daemons. It is not even the last step on the road to Dust, but it is an essential one. When they are reunited with their daemons, something is changed between them. They are still close, but there is a new edge to the relationship: an awareness of the fragility of their connection, but also of the strength that is the opposite side of that coin.

And that experience of death is not the last goodbye in the books. The final chapters are a series of partings, truly permanent ones that are heartbreaking in every possible way, and yet the story ends with hope. Because life is a series of goodbyes, but those partings are never the end. The people we leave behind—or who leave us behind—leave a piece of themselves with us.

Speculative Fiction is a Lens

Like the Amber Spyglass itself, it reveals to us the things we can’t see if we look directly at them. By sidestepping the direct in favor of symbols and metaphor, it captures those parts of reality that defy categorization. Like the journey from childhood to adulthood, and the bittersweet pain of discovering the gray areas. There’s a power in the written word and it’s amplified in those most vulnerable years. I’m sure the argument can be made for many genres, but for me, it was the very magic of fantasy (or technology of science fiction) that gave me the expansiveness I needed to encompass these experiences. It still does that to this day.

If there is one character in His Dark Materials who seems to be a signpost that growing up isn’t all bad, that having our daemon “settle” doesn’t mean we have to be set in our ways, it’s Dr. Mary Malone. A nun-turned-quantum-physicist who ventures out across the multiverse on a quest led only by the I Ching and her own curiosity, she is to my mind the moral heart of the story, or at least the interpreter of the moral heart. Mary is a model of resilience, of compassion, and of hope. I’ll leave you with her words:

“I stopped believing there was a power of good and a power of evil that were outside us. And I came to believe that good and evil are names for what people do, not for what they are.”

Announcements

If you, too, loved middle grade speculative fiction, my newest book comes out today from Chooseco. Share the power of speculative fiction with a middle-grade reader in your life. Or enjoy it for yourself!

I enjoyed this series as well and it helped inspire me to write a teen fantasy adventure series. My other series was for adults. I didn't know what to expect with this one, but writing it has been far more enjoyable than I expected.